Oana Stopariu for isolacinema.org

The biggest democracy of the world can anytime be placed on an equal position with Europe and even defeats when it comes to demography… Bollywood produces the biggest number of films in the world. Indian film production keeps the ascendant trend year after year, a possible social model proposed using the pattern of Holywood or just cosmopolitism and glamour. In such a strong competition, independent Indian filmmakers have a hard time surviving.

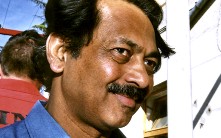

The presence of Girish Kasaravalli during the first edition of Kino Otok - Isola Cinema festival reveals a serious approach to social and political particularities of the biggest democracy in the world. There is unique style in his artistic attempt to tell the stories of his fellow Indians, caught in the transition of earthly life. Every one of his nine films, made in his 25 years of directing, masterfully captures the images based on his own screenplay. The entire structure of his films reveals itself to the eye of the spectator as gently as breathing. Izola`s Festival of African, Asian, Latin American and Eastern European cinema with friends brings to the public a facet of life that Girish Kasaravalli noticed through the lens of his camera.

The lone survivor of a group of intrepid directors that made New Kannada Cinema possible in the Seventies and Eighties, Girish Kasaravalli is a respected figure among Indian directors. Who would have thought that the teenager of 18, 19 years old, who got into the cinema business by mistake, would give up a pharmacist career to become one of the masters of the Indian seventh art? The first contacts with the cinema were not encouraging. The village Kasaravalli lies in the region of Malenadu in the federal state of Bangalore. In the summer there were only mythological long-feature films to be seen, produced most often by Telegu film industry. A large tent would be raised for 10 to 15 days in the center of the village with 5,000 inhabitants. Since Girish Kasaravalli`s father was the landlord, special chairs would be arranged for his family. Probably due to the fear that the public might get bored, socially inspired films were missing from the programs. The theatre would never screen Telegu or Tamil “socials". For some reason or other, the Hindu productions were also not appreciated, they were considered obscene and vulgar. English film was also totally unknown. Young Girish Kasaravalli would spend the nine month of the rainy season in the company of books. His grandfather, a renowned Sanskrit scholar, had introduced him to the deep perceptions of literature. The competition between cinema and literature would be categorically settled in the disfavor of cinema that could supposedly never match the artistry and depth of books. A change in this attitude came at the beginning of the Sixties, under the influence of K. V. Subanna, a highly respected thinker, critic and poet who would take film very seriously and spoke of his admiration of such filmmakers as Satyajit Ray or Akira Kurosawa, but also about individual masterpieces as “The Battleship Potemkin” and “Bicycle Thieves".

With only nine films made in the 25 years of his career, Girish Kasaravalli has a huge influence on the international cinematography. He has won the award for the best fiction film in India three times for “Ghatashraddh” ("The Ritual") in 1977, for “Tabarane Kathe” ("Tabara`s Story") in 1987 and for “Tahayi Saheba” in 1998. “Dweepa” ("The Island") completed last year marks another level in the work of Girish Kasaravalli, proposing new narrative and technical challenges. At the end of the film, Kasaravalli shows his admiration of a 12th century saint poetess AKKA Mahadevi by quoting a couplet from her works, a couplet that has some relevance to his film: “Still Water behind, full stream ahead/ What’s the way out, tell me/ A lake at the back, snare in front/ Can there be peace, tell me/ A body beyond seeking/ A bliss beyond matins/ Grant me Lord Channamallikarjuna“

Is there a special need for a film festival dedicated to the third world cinematography and what is your understanding of this figure of speech (’third world’ cinema)?

GK: I agree that there is a need for having a film festival which is dedicated solely to the third world cinema. Someone who views cinema as an exclusive activity, may not agree with this kind of segmentation, but someone who views it as an cultural expression, would get a different perspective. The culture interacts with the time and the people. It interplays with political and socio-economic conditions, and with existing traditions in art and in life.

What chances are there for its surviving in the vast process of globalization? How do you see its future?

GK: Globalization, in consideration to marketing strategies, would like to iron out all uniqueness and specificities. But film makers, like other artists, would like to go for the essence of life, would like to understand the principles of the mankind, would seek the logic, if there is one, of the universe. These projections would make the job of the film makers from the third world difficult. But haven’t we seen people who swim against the tide?

What are the major influences on your way of thinking and making films?

GK: Satyajit Ray, the towering figure of Indian Cinema, has cast a lasting influence on many Indian film makers of my time. A classicist in narration and construction, his profound understanding of the human nature and the world around him impressed me much. Similarly a writer in my language K. Shivarama Karanth has given me more insight into my field than anyone else.

What makes “Dweepa” different from your other films?

GK: The classical Indian poetry and folk arts have used elements in nature as metaphors of feminine principals, a concept which had attracted me since my childhood. I wanted to use that to interpret a modern day crisis. Dweepa was the result. As in our mythology here in this film nature becomes a character and intervenes. In this way it is quite different from my earlier films.

What was the most difficult time of your rich and extensive career?

GK: After each film I find myself exhausted and dejected. I find my representations partial and not holistic enough. To reequip myself is the most difficult time of my film career.

If you were a journalist, which would be the question you would propose to Girish Kasaravalli?

GK: What is life?

What would be the answer?

GK: I have not understood it myself. Film-making is a process to clarify my own doubts.

The raise against currents is something that Girish Kasaravalli is familiar with. 25 years of his career brought to cinephils all over the world a creative and constructive style and proved the strength and the value of cultural plurality regardless of social, political, historical or religious backgrounds.